II. The Protean Way

either log in or click here to purchase.

Log in here to access video.

Haven't purchased Eye of the Storm Leadership?

Starting Point / Bringing Down the Giraffe

In 1950 John Marshall, an anthropologist and film maker, received funding to study one of the migratory bands of Bushmen in Namibia. Known also as the !Kung or San people, the Bushmen are one of the last true hunting and gathering peoples left on the planet. They are what we all were 2,000 generations ago, and what in part we remain today. Marshall’s film, “The Hunters,� was, among other triumphs, the first use of color film in ethnographic cinematography and one of the first intimate portraits of the Bushmen.

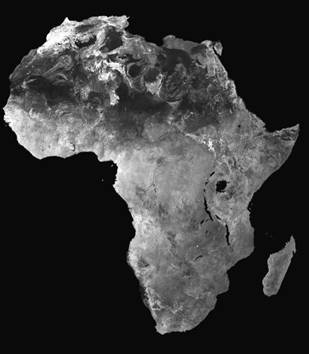

Satellite image of Africa, the birthplace of Homo Sapiens. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Satellite image of Africa, the birthplace of Homo Sapiens. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.For the next few days we follow them as they track the giraffe over the sere terrain of the Kalahari, nearly losing it in the surrounding hills and dry scrub. Finally, they find the animal in a stand of trees, weakened and abandoned by the rest of the herd. With arrows and spears they battle the still dangerous giraffe, bring it down, butcher it, and begin the journey home.

This is the thin shell of the narrative. Inside, there is another story, this one about four men working together, sometimes in counterpoint, to accomplish their objective. Look closely and unflinchingly and you see their individual qualities, their fears and idiosyncrasies, and something older and more timeless being played out on a hard landscape. The story within the story is about four functions in the body politic, each different, each needed, each a set of skills necessary to success.

All of them hunt but one among them is especially strong and competitive, able to pick up scents and follow trails when the others are baffled. In these moments, the others cede leadership to his knowledge and prowess. Another is a craftsman and technician, the one who fashions intricate and lethal arrows, the one who repairs spears, belts, and bows. At certain moments, others cede leadership to him. The third is a shaman, a holy man who performs ceremonies and who reminds the others of rituals that must be done if harmony in the world is to be maintained. The last is the band’s headman, the man who insists on cooperation when the others are squabbling, the one with the furrowed brow who bears the weight of potential failure on his shoulders, the one who urges them to work together until the goal is accomplished.

Marshall’s film is a taut, documentary portrait of our ancient and mysterious beginnings and shows us something universal about our humanity. It takes us to the heart of four ways of leading, four alternative approaches to solving problems, four disciplines, and four impulses for human success. One assumes there is not enough to go around and we are duty bound to secure our fair share. Another gives primacy to working as a group and achieving together what cannot be done individually. A third insists on doing what is right and linking everyday actions to higher purposes. The fourth honors our reasoning abilities to achieve practical solutions to pressing problems. All of them together are a prism, a lens that refracts our best intentions into the world.

The Rule of Four - The Fellowship of the Ring. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

The Rule of Four - The Fellowship of the Ring. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.To see this in a literary and cinematic mirror, look no further than J.R. Toilken’s Lord of the Rings. As the Hobbit Frodo Baggins sets off to destroy the dark powers of the ring, he is guarded on his flanks by a small but potent army of four. There is Legolas, the warrior, a prince of the elven kingdom of Mirkwood. Next to him is Gimli, a leader of the Middle-earth dwarves, famed as metal smiths, tool-makers, and craftsman. There is Aragorn, a human, destined to become the future King of Gondor. And there is Gandalf the wizard, a man whose mystical powers put him in touch with forces both natural and supernatural. Toilken called this strange gathering “the fellowship of the ring.� Marshall might have described the four Bushmen in those same terms.

11 Crucible

“I seldom think of politics more than eighteen hours a day.� Lyndon B. Johnson

Churchill in 1912, First Lord of Admiralty. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Churchill in 1912, First Lord of Admiralty. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

12 Dexterity

“Storms make trees take deeper roots.� Dolly Parton

|

|

This site managed with Dynamic Website Technology

from Mediate.com Products and Services |